“After a bird tied by a string flies here and there without finding a resting place, it finally settles down at the place where it is bound. Similarly, the mind, after flying here and there without finding a resting place, settles down in the breath, for the mind is bound to the breath.”

~ Chandogya Upaniṣad

The shape of life is infinitely malleable, and that malleability can flow in both limiting and expansive directions. To the degree that we become adapted to different systems of knowledge, structures of belief, and doctrines about how the world functions, our lives take on certain characteristics that are born out of these systems. Since we are all to varying degrees indoctrinated by our own cultural conditioning, personal experiences, political commitments, and visions of the good life, our breathing bodies become somatically attuned to that indoctrination. As a result, our awareness becomes similarly toned and transformed by the organizing impact of these various modes of situatedness and understanding.

I am not aware of any scientific studies that analyze the relationship between how individuals breathe and the cultural contexts in which they live, but it is consistent with the understanding of prāṇa we find in the yoga tradition that the attitudes of mind particular to a given culture will give rise to a corresponding style (or styles) of breathing. If the mind is bound to the breath, as the above passage from the Chandogya Upaniṣad suggests, then the shape of the mind will in various ways determine the texture of the breath. This texture may be perceived as subtle, but – as so many ancient and modern yogis and yoginīs have discovered – even a slight shift in the way we breathe can move mountains. As constellations of stress and agitation shift, the way we relate to our identity and our experience changes. In short, changing your breath can literally change your life.

There is thus a reciprocal causality between the mind and the breath. When the mind is calmed and clarified, the breath follows. When the breath is harnessed, softened, and deepened, the mind takes on a corresponding character of levity and lightness. In this way, the relative qualities of the breath and the mind are non-separable; one affects the other, and vice versa. While this might seem like a fairly banal observation – even basic from the perspective of those who have been practicing yoga for even a short time – it is nonetheless quite remarkable just how minimally acknowledged this connection between breath and mind is in the modern world. The breath, for most people, is just something the body does, and it tends to be largely ignored (unless one struggles with a respiratory condition like asthma). Even within some meditation communities, the breath is, at best, a supplemental practice – an adjunct to the ‘real’ work of harnessing the mind through visualization, mantra, or contemplative study.

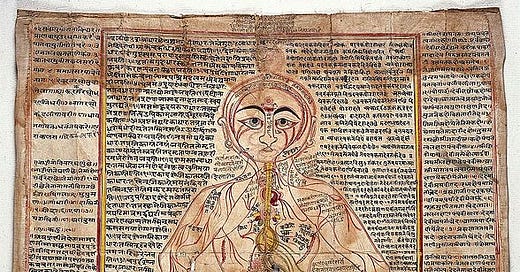

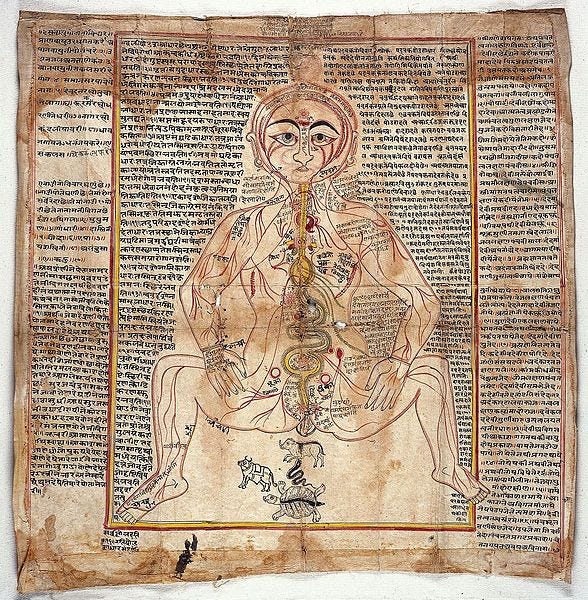

Various texts from the yoga tradition describe the relationship between the mind and the breath. In many descriptions of yogic practice, breathwork (prāṇāyāma) is depicted as a necessary limb (aṅga) of the practitioner’s ‘body of sādhana.’ While in the modern postural yoga class, there is an emphasis on aligning the breath systematically with bodily postures (āsana), in many texts we find prāṇāyāma outlined as an independent practice from posture. In the famous eight-limbed (aṣṭāṅga) yoga of Patañjali, āsana precedes prāṇāyāma in the order of limbs. While there are of course countless interpretations of how the eight limbs would have been (or should be) practiced – with some arguing for a sequential process while others argue for a simultaneous one – in some instances it is clear that āsana comes before prāṇāyāma because it is a more ‘gross’ (or sthūla) practice.

If we bracket out the yamas and niyamas (the first two limbs of ethical commitments and observances) for the sake of this consideration, it is easy to see how the remaining limbs map a trajectory from gross to subtle. I like to refer to this process as the “logic of prāṇa.” When our attention is externalized outward toward the world, our breath can easily become contracted in accordance with the hardening tendencies of a frenetic and increasingly agitated world. The breath carries and expresses the stress, anxiety, and other dispositions that constitute the psychological suffering of modern life. In this way, the breath becomes, for lack of a better term, ‘grossified.’ As we turn our attention toward the interior landscape, with the right scaffolding of knowledge and the appropriate techniques, our breath can become increasingly more subtle. In turn, our mind becomes more expansive, because the subtlety of breath and the luminosity of mind are two sides of the same yogic coin. As the mind becomes stilled – or is made more ‘sattvik’ – through a meditative process that embraces breathwork, this luminous mind becomes like a mirror capable of reflecting back to us what the yoga tradition calls the true Self, or puruṣa.

The reader might easily counter that, in the face of so many local and global challenges, stress and anxiety are understandable – and in some instances even necessary – responses to the age that we’re living in. After all, how could the ravages of war or the compounding extinctions of various species be related to in any other way than with rage, grief, or anxiety? While responding to this important question is beyond the scope of our reflections here, it is important, I think, to point out that the interiorizing process of sādhana does not have to mean a turning away from the world. It is quite the opposite. Much like eight hours of sleep is a necessary ‘turning away’ from the world to recharge our physical, emotional, and energetic batteries, similarly turning toward the subtle through practices of prāṇāyāma and meditation is an arguably necessary precondition for showing up in the world with wisdom, clarity, and an illuminated conviction. Anchoring ourselves in the subtle is therefore the strongest foundation for skillfulness in life.

Prāṇa, while often problematically translated simply as ‘breath,’ is better understood as the force of life itself – what French philosopher Henri Bergson referred to as the élan vital. It is the vital energy that animates and enlivens all beings. While it is present in literally everything, according to the Tantric tradition, it is constrained by the degree to which we are contracted by limiting beliefs, modes of identification, and contingent attitudes toward life. The process of sādhana, or contemplative practice, is one that first understands that there are possibilities of life that reflect a more intimate and expansive relationship with prāṇa. With this understanding in tow as a source of intellectual alignment and inspiration, the practitioner (or sādhaka) then employs those techniques that assist her in making these possibilities manifest.

The yogic techniques of prāṇāyāma and meditation thus become effective tools not only to embody the philosophy of yoga but also to deeply pursue a path of ‘subtlization’ that, according to the tradition, may eventually culminate in jīvanmukta – liberation in this lifetime.

If you are interested in joining us for an 8-week sādhana exploring the philosophy and practices of prāṇa and prāṇāyāma, go here for more information. The sādhana begins on Tuesday, January 21st, 2025 but anyone who joins after the start date will have immediate and ongoing access to all recordings available. While the offering is live, you can also engage with the offering as an on-demand experience. To learn about the full annual curriculum of Sādhana School, go here. To learn about our Yoga Teacher Training (YTT) program, go here.